NSF News Release: What’s killing trees during droughts? Scientists have new answers.

14 Aug 2017

News Source: NSF

Researchers find that carbon starvation and hydraulic failure kill drought-stricken trees.

As the number of droughts increases globally, scientists are working to develop predictions of how future parched conditions will affect plants, especially trees.

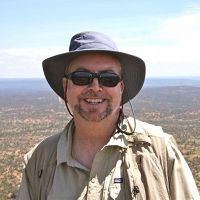

Ponderosa pines in Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico; the area has endured many droughts. Credit: William Hammond, Oklahoma State University

New results published today in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution by 62 scientists, led by Henry Adams at Oklahoma State University, synthesized research from drought manipulation studies and revealed the mechanisms by which tree deaths happen.

"Understanding drought is critical to managing our nation's forests," says Lina Patino, a section head in the National Science Foundation's (NSF) Division of Earth Sciences, which co-funded the study through its Critical Zone Observatories program. "This research will help us more accurately predict how trees will respond to environmental stresses, whether drought, insect damage or disease."

Adds Liz Blood, director of NSF's MacroSystems Biology program, which co-funded the research, "Droughts are simultaneously happening over large regions of the globe, affecting forests with very different trees. The discovery of how droughts cause mortality in trees, regardless of the type of tree, allows us to make better regional-scale predictions of droughts' effects on forests."

How trees respond to drought is important for models used to predict climate change. Plants take up a large portion of the carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere -- fewer trees means more CO2.

Sudden large-scale changes in plant populations, such as the tree die-offs observed worldwide in recent decades, could affect the rate at which climate changes.

Dead pine and fir trees in Sequoia National Park during the recent California drought.

Credit: Jordi Martinez-Vilalta

Current global vegetation models have faced challenges in producing consistent estimates of plant CO2 uptake, scientists say. The predictions vary widely depending on assumptions about how plants respond to climate.

One idea for improving the models is to base forest responses to climate change on how trees die in response to heat, drought and other stresses. But progress has been limited by disagreement over a central question: What, exactly, causes tree deaths?

In some cases, the deaths are a result of carbon starvation, in which trees close their pores, essentially starving themselves by blocking the entry of carbon, which is needed for photosynthesis. Or the culprit is hydraulic failure: the inability of a plant to move water from roots to leaves.

Adams explains that 99 percent of the water moving through a tree is used to keep stomata open. Stomata are the pores that let in carbon dioxide, allowing a tree to carry out photosynthesis.

Trees respond to the stress of drought by closing these pores. They then need to rely on stored sugars and starches to stay alive, and will die if these run out before a drought ends.

If a tree loses too much water too quickly, an air bubble (embolism) forms. The tree then has hydraulic failure and cannot transport water from the roots to the leaves, causing it to dry out and die.

The scientists found that hydraulic failure is universal when trees die, while carbon starvation is a contributing factor roughly half the time.

"Our findings help improve the understanding of how trees die, important in the context of climate change," says David Breshears of the University of Arizona, a co-author of the journal paper.

Adds Adams, "We produced a consensus view by bringing together many scientists with different perspectives." By finding new answers to a basic question -- what actually kills a tree in a drought? -- researchers can focus on effective solutions.

-NSF-

Media Contacts

Cheryl Dybas, NSF, (703) 292-7734, cdybas@nsf.gov

Brian Petrotta, Oklahoma State University, (405) 744-7497, brian.petrotta@okstate.edu

Ponderosa pines in Bandelier National Monument, New Mexico; the area has endured many droughts. Credit: William Hammond, Oklahoma State University

Dead pine and fir trees in Sequoia National Park during the recent California drought.

Credit: Jordi Martinez-Vilalta

News Source:

READ MORE from NSF >>

News Category:

RESEARCH

People Involved

CZO

-

Catalina-Jemez, INVESTIGATOR

-

Catalina-Jemez, INVESTIGATOR

-

Catalina-Jemez, INVESTIGATOR, COLLABORATOR

-

Catalina-Jemez, INVESTIGATOR

Publications

2017

A multi-species synthesis of physiological mechanisms in drought-induced tree mortality. Adams H.D., Zeppel M.J.B., Anderegg W.R.L., Hartmann H., Landhausser S.M., Tissue D.T., Huxman T.E., Hudson P.J., Franz T.E., Allen C.D., Anderegg L.D.L., Barron-Gafford G.A., Beerling D.J., Breshears D.D., Brodribb T.J., Bugmann H., Cobb R.C., Collins A.D., Dickman L.T., Duan H., Ewers B.E., Galiano L., Galvez D.A., Garcia-Forner N., Gaylord M.L., Germino M.J., Gessler A., Hacke U.G., Hakamada R., Hector A., Jenkins M.W., Kane J.M., Kolb T.E., Law D.J., Lewis J.D., Limousin J-M., Love D.M., Macalady A.K., Martinez-Vilalta J., Mencuccini M., Mitchell P.J., Muss J.D., O'Brien M.J., O'Grady A.P., Pangle R.E., Pinkard E.A., Piper F.I., Plaut J.A., Pockman W.T., Quirk J., Reinhardt K., Ripullone F., Ryan M.G., Sala A., Sevanto S., Sperry J.S., Vargas R., Vennetier M., Way D.A., Xu C., Yepez E.A., and McDowell N.G. (2017): Nature Ecology & Evolution 1: 1285–1291

Related News

NSF Discovery: Can an ancient ocean shoreline set the stage for a tropical forest of today?

13 Jul 2017 - Researchers at NSF Critical Zone Observatory and Long-Term Ecological Research sites are finding out.

NSF Discovery: Corn better used as food than biofuel, study finds

21 Jun 2017 - Scientists obtain comprehensive view of agricultural ecosystems

Explore Further