Jun 09, 2016

Natural faces and cut-polished facets of illustrious minerals shine with captivating opulence. These are commonly the minerals humans have touted as gifts from the Earth, to be cherished for generations. However, “all that glitters is not gold” as William Shakespeare once put it in The Merchant of Venice. A mineral far more important to the function of the Earth than pure gold and blue diamonds are feldspars. Feldspars compose the majority of the Earth’s crust (Nesse, 1999). They are not as famous as many of their companion minerals like quartz, but they are equally if not more important. So, why should anyone care about feldspars?

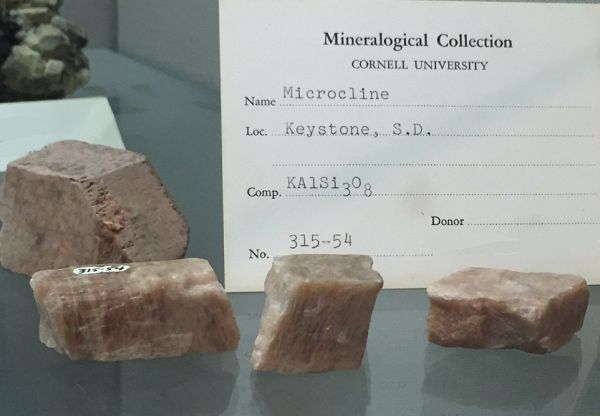

Due to the the atomic structure of feldspars, they can be found in many shapes and colors. To the common eye, feldspars are humble, generally lacking the luster gemstones possess, but they are beautiful in their own way, with pearly to shiny faces with distinct, geometric shapes. Feldspars are widely abundant because the temperature, pressure, and elements within the magmas and melts favor their formation. Feldspars are tectosilicate minerals, with a structure that allows for inclusion of many elements. The difference in the members of the feldspar families is due to the elements that are included in their structure. The alkali feldspars are predominantly potassium (K) and sodium (Na) (See image 2) while the plagioclase feldspars contain calcium (Ca) and sodium (Na).

Feldspars can be quite generous and allow for the inclusion of many other elements left over during the formation of the parent rock. Although the acceptance of different elements into the crystal structure may appear less than ideal for a perfect, homogeneous mineral, it is an great opportunity to learn about the molten rock from which it was formed! As feldspars grow, they can have chemically unique zones within their crystals, corresponding with chemical changes in the magma, known as crystal zonation. Thus, elements found in the core of the mineral but absent on the exterior of feldspar can be used to infer what other minerals were growing in the melt. Showing the depletion of different elements as the minerals grew in the cooling melt.

At the surface of the Earth, feldspars are no longer stable and begin to weather away, releasing essential plant nutrients and forming important secondary clay minerals. As mentioned earlier, feldspars contain many nutrient metals that become available for plants during weathering in the soil. Many of the nutrients present in some of the most highly weathered soils of the southeastern United States are from the remaining feldspars. Moreover, feldspars are commonly responsible for the majority of alkalinity in stream waters, which is an essential property for healthy aquatic ecosystems (check out Mast and others, 1990). Lastly, feldspars commonly weather to clay minerals (such as kaolinite or illite). Clay minerals, commonly derived from weathered feldspars, are important in agriculture for promoting water and nutrient retention in soil and may also be mined for a wide array of human uses including ceramics to toothpaste. For these reasons, feldspars are far more important to life in the Critical Zone than quartz and diamonds!

The weathering of feldspars can tell us about their soil environment. One example is a study conducted by Dr. Rebecca Lybrand at the Santa Catalina Mountain - Jemez River Basin Critical Zone Observatory. In her study (Lybrand and Rasmussen, 2014), Dr. Lybrand examined how feldspar weathering was influenced by moisture, temperature, and vegetation by comparing minerals from a cool, moist conifer forest to those from a hot, desert scrub. She observed that sodium (Na) had been more extensively lost at the cool, moist conifer stand than the warmer, desert scrub sites. In addition to the overall chemistry of the soil, these changes were visually seen using a scanning electron microscope. In the images, she noted that feldspars at in the desert area had weathered exteriors while feldspars from the forested area showed deep weathering throughout the mineral. In essence, feldspars in moist forests will be weathered away much faster than their counterparts in drier areas of the landscape.

Feldspars are but one of the many different minerals that comprise the rocks of the critical zone. You can learn more about other common and rare minerals here: http://geology.com/minerals/ or http://www.mindat.org/ and learn about their economic importance here: http://minerals.usgs.gov/

Have any questions swirling in your noodle about the rock, soil, water, fauna, or flora of the critical zone? Send them our way at Askcriticalzone@gmail.com.

Science on!

Justin Richardson

Critical Zone Observatory Post-Doctoral Fellow

References

Lybrand R.A., Rasmussen C., 2014. Linking soil element-mass-transfer to microscale mineral weathering across a semiarid environmental gradient. Chemical Geology 381:26 – 39.

Mast M.A., Drever J.I., Baron J., Chemical weathering in the Loch Vale Watershed, Rock Mountain National Park, Colorado. Water Resources Research 26: 2971 – 2978.

DOI: 10.1029/WR026i012p02971

Nesse, W.D., 1999. Introduction to Mineralogy (No. 549 NES) Oxford University Press, 1999.

Image 1. A alkali feldspar exhibiting twinning as seen through a electron microscope.

Image 2. Microcline, one of the alkali feldspar end-members, rich in potassium (K).

Justin B. Richardson

CZO INVESTIGATOR, STAFF. National Office outreach officer, Former CZO Post-Doctoral Fellow. Specialty: Soil biogeochemistry of plant-essential and toxic metals.

Geochemistry / Mineralogy Soil Science / Pedology EDUCATION/OUTREACH General Public K-12 Education

COMMENT ON "Adventures in the Critical Zone"

All comments are moderated. If you want to comment without logging in, select either the "Start/Join the discussion" box or a "Reply" link, then "Name", and finally, "I'd rather post as a guest" checkbox.

ABOUT THIS BLOG

Justin Richardson and his guests answer questions about the Critical Zone, synthesize CZ research, and meet folks working at the CZ observatories

General Disclaimer: Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations presented in the above blog post are only those of the blog author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. CZO National Program or the National Science Foundation. For official information about NSF, visit www.nsf.gov.

Explore Further