Pelletier & Swetnam, 2017

Asymmetry of weathering-limited hillslopes: the importance of diurnal covariation in solar insolation and temperature

Pelletier J.D. and Swetnam T.L. (2017)

Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 42(9): 1408–1418

-

Catalina-Jemez, INVESTIGATOR

-

Catalina-Jemez, INVESTIGATOR

Abstract

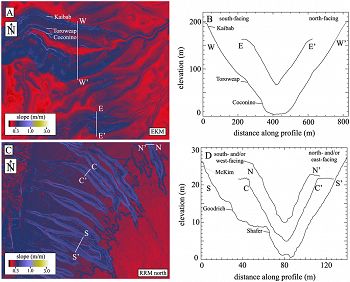

Examples of hillslope asymmetry. (A) and (B) In the northern portion of the EKM, profiles of higher relief result in greater asymmetry. Profile W-W′ has a S-facing segment in which the Kaibab, Toroweap, and Coconino units all form cliffs. The N-facing side has no cliffs. A lower-relief profile (E–E’) is more symmetric. (C) and (D) In the northern portion of the RRM, three profiles are compared with variable orientations. The valley oriented most nearly E–W has the profile (S–S′) with the largest asymmetry, with prominent cliffs formed on the McKim, Goodrich, and Shafer units. The profiles become more symmetric as the orientation of the valley becomes more N–S.

Hillslope asymmetry, i.e. variation in hillslope form as a function of slope aspect and/or mean solar insolation, has been documented in many climates and geologic contexts. Such patterns have the potential to help us better understand the hydrologic, ecologic, and geomorphologic processes and feedbacks operating on hillslopes. Here we document asymmetry in the fraction of hillslope relief accommodated by cliffs in weathering-limited hillslopes of drainage basins incised into the East Kaibab Monocline (northern Arizona) and Raplee Ridge Monocline (southern Utah) of the southern Colorado Plateau. We document that south- and west-facing hillslopes have a larger proportion of hillslope relief accommodated by cliffs compared with north- and east-facing hillslopes. Cliff abundance correlates positively with mean solar insolation and, by inference, negatively with soil/rock moisture. Solar insolation control of hillslope asymmetry is an incomplete explanation, however, because it cannot account for the fact that the greatest asymmetry occurs between southwest- and northeast-facing hillslopes rather than between south- and north-facing hillslopes in the study sites. Modeling results suggest that southwest-facing hillslopes are more cliff-dominated than southeast-facing hillslopes of the same mean solar insolation in part because potential evapotranspiration rates, which control the soil/rock moisture that drives weathering, are controlled by the product of solar insolation and a nonlinear function of surface temperature, together with the fact that southwest-facing hillslopes receive peak solar insolation during warmer times of day compared with southeast-facing hillslopes. The dependence of water availability on both solar insolation and surface temperature highlights the importance of the diurnal cycle in controlling water availability, and it provides a general explanation for the fact that vegetation cover tends to exhibit the greatest difference between northeast- and southwest-facing hillslopes in the Northern Hemisphere and between southeast- and northwest-facing hillslopes in the Southern Hemisphere.

Citation

Pelletier J.D. and Swetnam T.L. (2017): Asymmetry of weathering-limited hillslopes: the importance of diurnal covariation in solar insolation and temperature. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 42(9): 1408–1418. DOI: 10.1002/esp.4136

This Paper/Book acknowledges NSF CZO grant support.

This Paper/Book acknowledges NSF CZO grant support.

Explore Further