Critical Zone Profile - RACHEL GALLERY (microbial biologist, assistant professor)

13 Mar 2015

Assistant Professor, School of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of Arizona.

Plant-microbe interactions and feedbacks are important but cryptic components of how ecosystems function and respond to change. Despite their fundamental importance, the distributions of microbial genotypes are largely unknown, their interactions with plants and animals are not well understood, and the complexity of microbial communities is too often inelegantly over simplified. As we consider the threat of species loss and how plant communities will continue to shift in response to rapidly altered temperature and precipitation patterns, the need to understand plant-microbe feedbacks emerges as a critical focus.

Recording soil temperature and vegetation cover data in the Santa Rita Experimental Range, Arizona. Photo credit: Amy Kwiecien.

“We can and should talk to our state representatives – as scientists and as citizens – to show them the faces of researchers engaged in answering questions that address soil and water quality. These are national priorities.” – Rachel Gallery

Most of Earth’s biodiversity is invisible. Trillions of microorganisms drive our global nutrient cycles, influence the security of our food, and impact the health of our bodies. Microorganisms were Earth’s first ecosystem engineers – originally creating the conditions that sustain life and ultimately determining the diversity of organisms in our biosphere. Microbes define soil health and ecosystem services and can tip the competitive balance among neighboring plant species by controlling which individuals will grow and which will fail. Microorganisms are crucial elements that can drive and influence the outcome of ecosystem function, services, and conservation strategies. They are critical to ecosystem resiliency, especially in the context of climate change and the conservation challenges we currently face.

My research group studies the ecology of soil microbes. Working across a range of ecosystems from lowland forests, to high elevation conifer forests, to semi-arid grasslands, we use field-based experiments, microbiological techniques, and contemporary genetic tools to test the effects of plant-microbe interactions on plant and microbe community diversity, understand how environmental shifts will alter these interactions, and accurately predict the subsequent impacts on ecosystem function.

CRITICAL ZONE OBSERVATORIES (CZO)

The CZO is a multidisciplinary network of scientists and students. Our meetings bring all the “ologists” to the table, including geomorphologists, hydrologists, climatologists, ecologists and we all speak a different - not language, exactly, but dialect. The value of interdisciplinary research is its potential to tackle research questions that are greater than the sum of their parts. The challenge is in coordinating so many different perspectives.

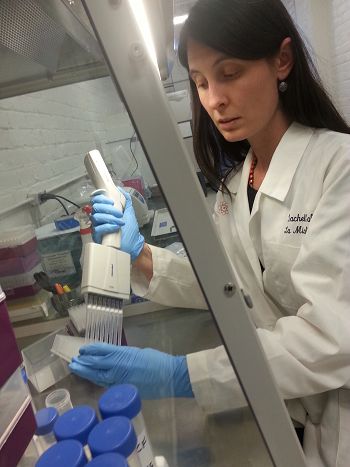

Extracting DNA from soil samples to measure changes in the identities and diversity of bacteria, archaea, and fungi in soils after the Thompson Ridge Fire in Jemez, New Mexico. Photo credit: David Moore.

By continuing to fund and invest in CZO science infrastructure, the National Science Foundation is establishing critical zone science as a national priority. The CZO attracts outstanding graduate students and postdocs who set a standard of research excellence. The CZO national office distributes funds for cross-CZO initiatives and, as just one of many examples, we have now established a Biogeochemistry working group to coordinate sampling and analysis efforts.

CZOs can improve our understanding and management of natural resources by expanding the timescale with which we consider and approach management issues. As an example, soils are formed over hundreds of thousands of years, whereas human activity that removes soils or alters soil resources – including urbanization, agriculture, and recreation – happens on much shorter timescales. How can we reconcile this? Led by Jason Field, the Jemez-Catalina CZO recently published an article that expands our perspective of ecosystem services to include critical zone processes and timescales (See News Story about the publication)

My students and I are very much engaged in outreach. Our job is made easy by the fact that kids love playing in the dirt. My research group works with the University of Arizona Sky School to engage K-12 students in geology and soil science research projects that get them outside and their hands dirty.

:: By Linda Copman, staff writer ::

Recording soil temperature and vegetation cover data in the Santa Rita Experimental Range, Arizona. Photo credit: Amy Kwiecien.

Extracting DNA from soil samples to measure changes in the identities and diversity of bacteria, archaea, and fungi in soils after the Thompson Ridge Fire in Jemez, New Mexico. Photo credit: David Moore.

Publications

2015

Critical Zone Services: Expanding Context, Constraints, and Currency beyond Ecosystem Services. Field J.P., Breshears D.D., Law D.J., Villegas J.C., López-Hoffman L., Brooks P.D., Chorover J., Barron-Gafford G.A., Gallery R.E., Litvak M.E., Lybrand R.A., McIntosh J.C., Meixner T., Niu G-Y., Papuga S.A., Pelletier J.D., Rasmussen C.R., and Troch P.A (2015): Vadose Zone Journal 14(1)

Discipline Tags and CZOs

Biology / Ecology

Biology / Molecular

Biogeochemistry

National

Catalina-Jemez

Related News

Explore Further