Richter et al., 2020

Soil production and the soil geomorphology legacy of Grove Karl Gilbert

Richter, Daniel D., Martha-Cary Eppes, Jason C. Austin, Allan R. Bacon, Sharon A. Billings, Zachary Brecheisen, Terry A. Ferguson, Daniel Markewitz, Julio Pachon, Paul A. Schroeder, Anna M. Wade (2020)

Soil Science Society of America Journal 84(1): 1-20

-

Calhoun, INVESTIGATOR

-

Calhoun, INVESTIGATOR

-

Calhoun, INVESTIGATOR

-

Calhoun, INVESTIGATOR

-

Calhoun, GRAD STUDENT

-

Calhoun, COLLABORATOR

-

Calhoun, INVESTIGATOR

-

Calhoun, COLLABORATOR, GRAD STUDENT

-

Calhoun, INVESTIGATOR

-

Calhoun, GRAD STUDENT

Abstract

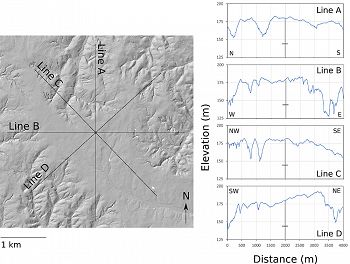

A LiDAR slope map of the Calhoun Critical Zone Observatory, near Cross Keys and Sedalia, SC. Here we show the broad, low curvature, nearly level interfluve and the location of the residual regolith and the 65-m deep corehole in the On the right, 4000-m long elevational transects are illustrated with the vertical corehole shown as a vertical line with a horizontal cross-hatch at the base of the regolith at 38-m, the base of the fractured weathering granitic gneiss bedrock. Nearly all of this landscape is eroded, much seriously so. Nearly every channel in the LiDAR image is deeply incised or gullied due to historic agriculture.

Geomorphologists are quantifying the rates of an important component of bedrock's weathering in research that needs wide discussion among soil scientists. By using cosmogenic nuclides, geomorphologists estimate landscapes’ physical lowering, which, in a steady landscape, equates to upward transfers of weathered rock into slowly moving hillslope-soil creep. Since the 1990s, these processes have been called “soil production” or “mobile regolith production”. In this paper, we assert the importance of a fully integrated pedological and geomorphological approach not only to soil creep but to soil, regolith, and landscape evolution; we clarify terms to facilitate soil geomorphology collaboration; and we seek a greater understanding of our sciences’ history. We show how the legacy of Grove Karl Gilbert extend across soil geomorphology. We interpret three contrasting soils and regoliths in the USA's Southern Piedmont in the context of a Gilbert-inspired model of weathering and transport, a model of regolith evolution and of nonsteady systems that liberate particles and solutes from bedrock and transport them across the landscape. This exercise leads us to conclude that the Southern Piedmont is a region with soils and regoliths derived directly from weathering bedrock below (a regional paradigm for more than a century) but that the Piedmont also has significant areas in which regoliths are at least partly formed from paleo-colluvia that may be massive in volume and overlie organic-enriched layers, peat, and paleo-saprolite. An explicitly integrated study of soil geomorphology can accelerate our understanding of soil, regoliths, and landscape evolution in all physiographic regions.

Citation

Richter, Daniel D., Martha-Cary Eppes, Jason C. Austin, Allan R. Bacon, Sharon A. Billings, Zachary Brecheisen, Terry A. Ferguson, Daniel Markewitz, Julio Pachon, Paul A. Schroeder, Anna M. Wade (2020): Soil production and the soil geomorphology legacy of Grove Karl Gilbert. Soil Science Society of America Journal 84(1): 1-20. DOI: 10.1002/saj2.20030

This Paper/Book acknowledges NSF CZO grant support.

This Paper/Book acknowledges NSF CZO grant support.

Associated Files

Soil production and the soil geomorphology legacy of Grove Karl Gilbert

(1 MB pdf)

full preprint

Explore Further