Ecology From Treetop To Bedrock: Human Influence In Earth’s Critical Zone

17 Jul 2015

News Source: Ecological Society of America

An Organized Session On Critical Zone Ecology At The 100th Annual Meeting Of The Ecological Society Of America August 9-14, 2015 In Baltimore, Md.

On the high slopes of the Eel River watershed on California’s North Coast Range, large conifers sink their roots deep through the soil and into fractures in the mudstone bedrock, tapping water reserves that scientists are only recently learning to appreciate. These unexpected reservoirs may provide resiliency to the Eel River ecosystem in intensive droughts, such as the one California is now experiencing.

“The way water is stored, intercepted, and released is critical to drought and extreme floods. Researchers are getting surprises about how important the deep fractured bedrock can be,” said Mary Power, a stream ecologist at the University of California at Berkeley and an investigator at the Eel River Critical Zone Observatory, one of ten Critical Zone Observatories (CZOs) funded by the National Science Foundation that bring together geologists, hydrologists, microbiologists, climate scientists, ecologists, and more to work on research questions that tend to lie at the interface of their disciplines.

Power will report on effects on interactions of vegetation and the underlying geology on salmon and river ecosystems as part of an organized series of talks showcasing Critical Zone Ecology at the 100th Annual Meeting of the Ecological Society of America in Baltimore, Md. this August 9–14.

“How flashy or spongy will the watershed be when it rains? Will the storm runoff be stored, and infiltrate, or flash off downslope? What are the water storage and slow release dynamics that will—please, please—keep us going through this drought?” These are pressing questions that the interdisciplinary team is working on at the Eel River CZO, Power said.

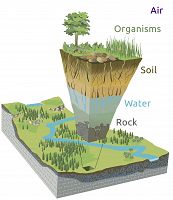

Large conifer trees span the critical zone between bedrock and atmosphere, in which the movements and actions of water, air, and a complex web of living organisms shape and transform the physical crust of the earth. Water can be stored in weathered bedrock, changed chemically during storage, and drawn up to the atmosphere by big trees. It flows down through rock fractures to supply downslope surface waters. In this relatively narrow space lie all the life-sustaining resources supporting terrestrial life on earth. Earth’s critical zone supports human societies and is deeply impacted by the actions and activities of those societies.

“To ecologists, the Critical Zone is an ecosystem, a watershed,” said Kathleen Lohse, who directs the new Reynolds Creek Critical Zone Observatory in southwest Idaho and co-organized the meeting session on critical zone ecology. “I’m trained as an ecosystem scientist. My specialty is soil. Over the years I’ve come to appreciate the term ‘critical zone’ and the inclusive perspective it brings. It’s not owned by ecology, geology, soil science, or any other discipline. It’s shared.”

Originally conceived by earth scientists to describe the overlooked “vertical dimension” of the water cycle, critical zone science has grown as a truly interdisciplinary field. But, though living organisms affect the water cycle as profoundly as the characteristics of the underlying geology, ecologists have been late to the party – the term “critical zone” is unfamiliar to many.

“One reason why ecology hasn’t heard as much about the critical zone is that it’s based in the earth sciences. We need to bring more ecologists to play in the same sandbox,” said Lohse.

Lohse, an associate professor of soil and watershed biogeochemistry at Idaho State University, and Whendee Silver, a professor in ecosystem ecology at UC Berkeley and an investigator at the Luquillo Critical Zone Observatory in Puerto Rico, organized the session on “Ecology in the Critical Zone” at the 100th Annual Meeting to bring critical zone science to the attention of the ecological community.

“The goal of this whole session is to put the CZOs on the radar and get ecologists to see them as resources and to propose and conduct research,” said Lohse. They are typically much larger in scale than the traditional Long Term Ecological Research sites, and have the potential to allow ecologist to scale up small, intensive experiments and form a bridge to large scale modeling studies, she said.

Speakers include Power, Dawson, and representatives from the other CZOs. The observatories investigate a spectrum of biological, chemical, climatic, geological, and hydrologic conditions across the continental United States and Puerto Rico, but are also organized around specific research questions, from soil carbon storage in mountain forests (Reynolds Creek, ID) to erosion on intensively managed agricultural lands (Clear Creek, IA) to the legacy of cotton cultivation on resurgent pine stands in the Southern Piedmont (Calhoun, SC).

Dan Richter, director of the Calhoun CZO in South Carolina and a professor at Duke University, will also speak on the “One physical system” encompassed by the ecosystem and critical zone concepts at the Annual Meeting, during a session of talks on ecosystem function on the afternoon of Monday, August 7.

“We tried to get a relatively even distribution across the CZOs and to get the speakers to highlight some of achievements that have come out of their field of ecology, and the gaps where we really need ecologists to help us understand the critical zone,” said Lohse.

Gaps include the response of microbial communities to wildfire and climate change, contributions of roots and underground biological processes, and the activities and population dynamics of animals like gophers, beavers, and earthworms.

“If you walk across the Reynolds Creek CZO you see so much gopher and mole activity. There has been some work looking at their transfer of soil and carbon downslope, but you need to understand the population dynamics of those communities to really model it. They are critical players, particularly in Reynolds,” said Lohse.

Reynolds Creek is composed of about 70 percent public land administered by the Bureau of Land Management and 30 percent privately owned land, managed as a working landscape. The observatory is preparing to record the effects of a scheduled 12,000 acre prescribed burn in the experimental watershed in early fall, designed to clear encroaching Juniper from the sagebrush steppe.

“Stakeholders are really excited about this burn. They want to reduce fuel and increase forage,” said Lohse. “We’ve been establishing permanent vegetation plots on north and south facing plots in the watershed to monitor how the fire changes soil carbon quality and quantity.”

Water dynamics in the critical zone are profoundly affected by the sudden, massive changes to vegetation cover and soil brought by wildfire. The choices that we make to suppress or encourage fire, graze livestock or convert land to farm fields, clear-cut or plant mountain slopes, and divert water or leave it in natural flows, all play out in the dynamics of the critical zone.

In the dry heat of late summer in California, cold can be as valuable commodity as the water itself. Water that is too warm can be a big problem for fish and other animals. Sufficient cool groundwater flowing down through mountain bedrock and entering into streams can off-set low water levels and prevent the warm, stagnant conditions that stress salmon and encourage the growth of toxic algae. Decisions about how much cool water people divert from the system could tip the balance for the ecosystem, Power said.

Choices that people and communities make about the use of land for agriculture, living spaces, and industry have profound effects on the critical zone – but this also suggests that communities may be empowered by good critical zone science to manage surface cover and land use to enhance the resilience and sustainability of watersheds and water reserves.

News Source:

READ MORE from Ecological Society of America >>

News Category:

RESEARCH

Explore Further